Tea ceremony at ‘Kokoro’: ‘Cup of Humanity’ overfloweth

In a country steeped in spirituality and religion, India could have introduced ‘tea ceremony’ the way China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan did and this could have been used as a unique protest against even colonialism during the Swadesi movement, feels Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay, poet, calligrapher and tea-artist.

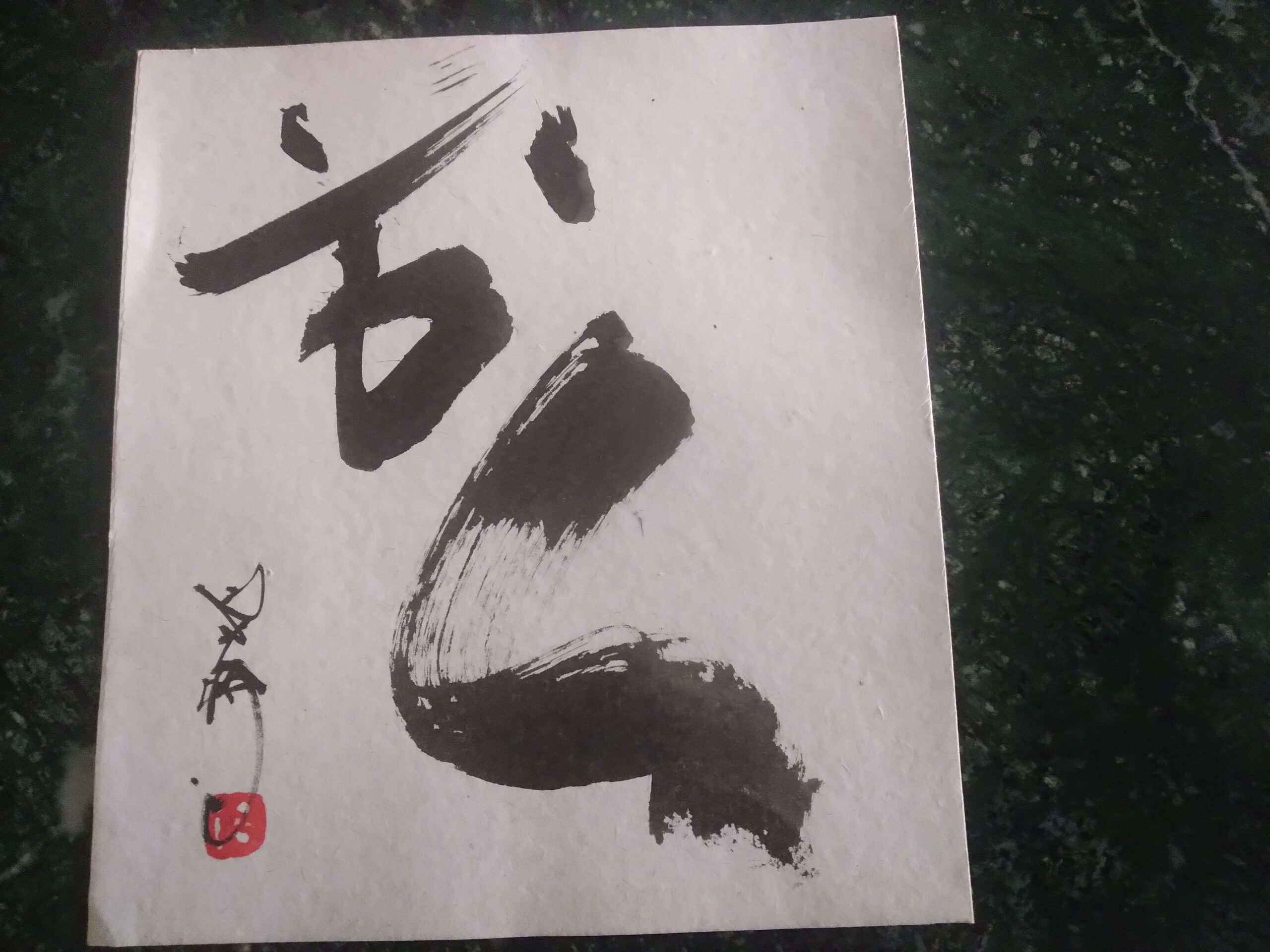

An austere yet elegant room with wooden flooring and an exquisite calligraphy framed on the wall form a fitting tokonoma or alcove to the tea-making tools tastefully arranged as a centerpiece in Bandyopadhyay’s ‘Kokoro House’ (‘kokoro’ meaning ‘heart’ in Japanese ) at Purva Palli, Santiniketan.

Nilanjan Bandyopadhyay’s ‘Kokoro House’ in Santiniketan

Nilanjan prepares tea for his guests

Bandyopadhyay, a Japanophile and an expert on Tagore and Japan, has introduced a unique ‘tea ceremony’ at his ‘Kokoro House’ combining the Chinese, Japanese, Taiwanese and Korean ways primarily for his guests coming from different parts of the world to promote peace and harmony.

In 1999, Bandyopadhyay went to Japan for the first time and since then he wanted to build a ‘Kokoro House’ (a house inspired by Japan). The house, designed by young Japanese architect Kengo Sato together with Milon Dutta, was finally completed in December 2018.

Tea was imported to India from China via Europe in 1839. Indians follow the European tea-drinking tradition. However, no spiritual and aesthetic aspects are associated with tea-drinking in India. Tea, in Indian culture, is considered either a popular drink, an addiction or simply a need to slake one’s thirst.

“Serving tea for my guests with reverence and achieving spiritual fulfillment, savoring aesthetic pleasure and fostering friendship, are the destination of my tea ceremony,” says Bandyopadhyay.

He was in a dilemma as to how he would name this ‘celebration’. “In China and Japan, the same character is used to write the word ‘cha’. “Even though the word ‘tea’ has an association with China and Japan, I wanted to infuse an Indianness to this ‘celebration’,” he says. “After much thought, I’ve named it ‘Bodhi Cha’– ‘bodhi’ in Sanskrit and ‘cha’ in Chinese and Japanese alphabets.”

Tea-making tools

‘Tea ceremony’ requires not only some specific tools, but also a particular method. Recounting the rituals of the ceremony, Bandyopadhyay says, before the guests arrive, the host will arrange flowers in a vase, burn incense and keep all tools needed for tea-making in a clean and tidy room. The guests will wait at a distance. One part of the arranged flowers will point to the heaven, the middle portion of the arrangement will point to humanity and the other part will point to the ground in such a way that the entire arrangement will represent heaven, man and earth respectively.

A tray will be placed between the guests and the host in such a way so that hot water of the tea will seep through different small holes of the tray and collect in a container. For the host and the guests, a small tea pot and very small cups are needed. Guests will be urged to take seats by ringing of a bell. The host will take his seat in front of the guests only after they are seated.

There should not be more than six guests at a time.

Even though there are some regional differences in tea-drinking across India, there’s, as it were, a unity in them which may be termed as ‘need’. Unfortunately, the tradition of tea-drinking in India has never gone beyond the ‘need’ to become an ‘art’ which is found in China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Influenced by the British, the habit of tea-drinking with milk and sugar in India is actually ‘soulless’ which has taste and flavor but no heart (of its own), he says.

In the ancient times, tea used to keep Buddhist monks awake during meditation in China and it spread to Japan through them. In China and Japan, tea-drinking is a ‘celebration’. The objective of the ‘celebration’ was to prepare tea and serve it with reverence, devotion and self-control, aesthetic pleasure and spiritual fulfillment to foster harmony, friendship, oneness with guests, Nature, environment and even with the tools for tea-making. In ‘tea ceremony’, one comes across Taoism, ideas of Confucius and Buddha: creating profound connection between man and Nature, acknowledging the mystery of the universe.

In his widely acclaimed book, The Book of Tea, the great Japanese scholar and art critic Okakura Kakuzo, said: “The culture of tea-drinking in Japan is, in fact, Taoism in disguise.”

In the sixteenth century, world-famous Japanese scholar Sen no Rikkyu added a whole new dimension to the tea-drinking tradition that was born out of his wabi-sabi philosophy that celebrates the beauty of simplicity, imperfection and incompleteness. Linking Japanese tea-ceremony to simplicity, austerity and rugged beauty, he introduced the establishment of a tiny, simple tea-house, bamboo flower vases, art, calligraphy, poetry, tea spoons, tea cups and other tools —- all created with a touch of magical melancholy and dignified austerity.

The small, beautiful and modest Japanese tea-houses are surrounded by a slightly disarrayed garden. Guests wash their hands with water in a stone basin, make their way through this garden with a calm mind, enter with bent heads through a narrow door and step into the all-pervading silence of the humble tea-room, shorn of opulence and tacky grandeur. Herein lie purity, reverence, harmony and the opportunity to discover oneself as a part of this infinite universe.

“Sen no Rikkyu taught the world to look for beauty in simplicity and did away with the gorgeous and gaudy tea-making tools used in China. Instead he used simple yet aesthetically unique tools,” says Bandyopadhyay.

His tea rooms became smaller and more austere as a mark of silent protest against the increasing megalomaniac tendencies of his contemporary ruler, he says.

Okakura believed that true beauty encompassed both body and mind and until this state is achieved one has no right to talk about beauty. That is why exponents of tea-making wanted to become more than artists — the art itself, Bandyopadhyay says.

Bandyopadhyay’s Bodi Cha ceremony that resembles the tea ceremony known as ‘Gongfu’ cha, is remarkably different from the ‘tea ceremony’ in Japan known as ‘sado’ or ‘cha no yu’. Green tea powder is used in Japanese ‘tea ceremony’ instead of tea leaves used by the Chinese. Tea pots used in Japan for everyday tea-drinking are also comparatively wide and deep. No tea pots are used in a traditional Japanese tea ceremony as a tea bowl and a whisk are used to prepare thick, powdered green tea.

Tea pet ‘Ananda’

‘Cup of Humanity’

Among the various utensils of tea-making, an interesting one is the tea-pet ‘Ananda’—a silent companion and well-wisher of the tea-maker and his guests.

Another tool worth mentioning, as introduced by Bandyopadhyay, is the ‘Cup of Humanity’—a tiny cup capable of holding a few drops of water, dedicated to the ancestors, guru and the tea producers.

Rabindranath Tagore, says Bandyopadhyaya, understood the spiritual power of this ‘tea ceremony’. In his first trip to Japan in 1916, Tagore went to the house of Ryuhei Murayama, the owner of the newspaper, The Asahi Shimbun, to attend a ‘tea festival’. A mesmerized Tagore wrote in Japanjatri: “Tea-making is all about practising abstinence, complete control over one’s body and mind, achieving perfect calmness of mind and embracing all that is beautiful in oneself….Immersing oneself in the profundity of beauty away from disorder and intemperance is the essence of the tea celebration.”

He realized the pure and unalloyed beauty of the celebration that protects one’s mind from selfishness and materialism. Tagore wanted to make the Chinese and Japanese ways of tea-drinking a part of Santiniketan’s aesthetics and that is why he, aided by Chinese poet Xu Zhimo, had set up ‘Xu Zhi mo cha chokro’ (the Xu Zhimo Tea Circle) which was later shifted to ‘Dinantika’, says Bandyopadhyay.

A calligraphy ‘Shyun ka shyu to’ (meaning ‘spring summer autumn winter’) by Kofude Ougai

Calligraphy by Nilanjan